Do you want to explore the fascinating world of piano chords?

Don’t spend years playing piano without truly understanding what chords are. That would be a mistake—chords are an essential part of music. Music is emotion, and chords are the fundamental tool for expressing it. They have the power to evoke joy, sadness, mystery, or resolve tension in a composition. Chords provide harmonic context to a melody—they are the foundation on which a song is built.

So, without further ado, let’s dive into the wonderful universe of piano chords.

What are chords on the piano?

Think of chords like the legs of a table or the foundation of a house—they’re the structures on which you build music. But what exactly is a chord? A chord is simply a group of notes played at the same time. That’s it! You already know the basics. But of course, there’s much more to discover.

How are chords formed?

Let’s start from the beginning: how are chords formed? In general, chords are made up of at least three notes. These groupings of notes are known as triads.

Why at least three? As we mentioned before, think of chords like a table: with just one leg (or one note), it would be unstable. With two legs, a bit better, but still unusable. But with three legs, the table stands strong—and now you can build on it.

Some chords contain more than three notes, which adds interesting musical richness. But let’s leave those for later. For now, we’ll focus on understanding the fundamentals: a chord is a group of notes.

Notes and Intervals

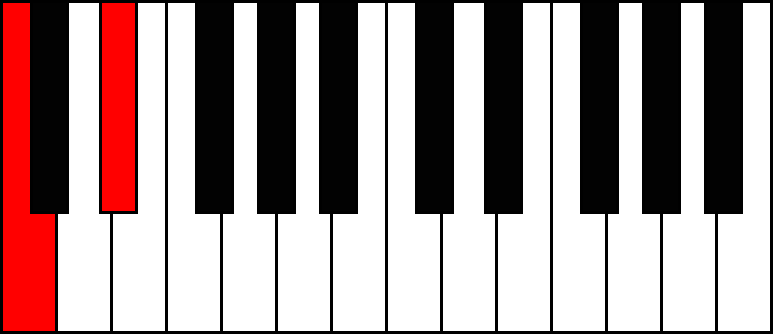

On your piano keyboard, there are different notes (88 on a full-sized piano) with different pitch levels. To form a chord, you know you need at least three notes—but you can’t just pick any random ones. There are rules, and those rules are based on intervals.

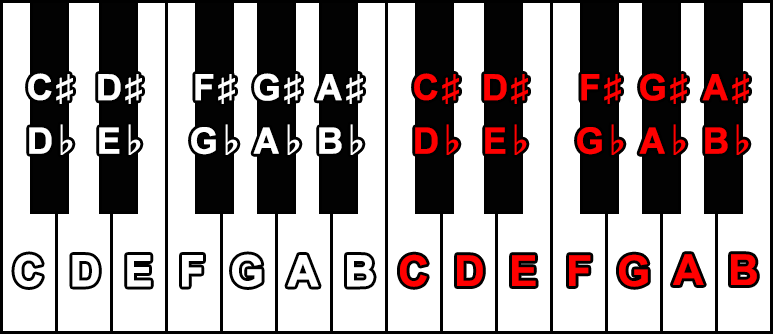

But don’t worry—it’s simpler than it sounds. Intervals are just the distance between notes. On the keyboard, you’ll see 7 white keys repeating from C to B, plus 5 black keys with names like sharps and flats. In total, there are 12 distinct notes repeated across the keyboard.

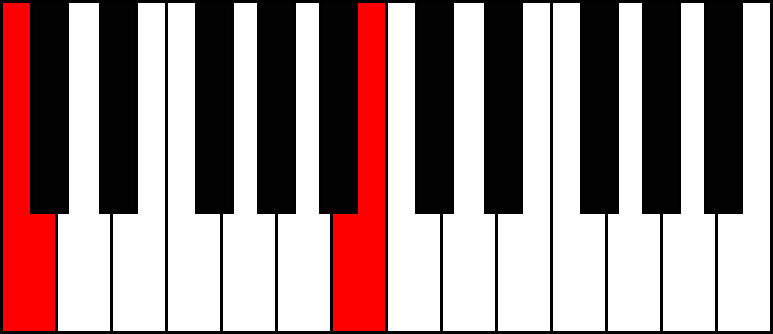

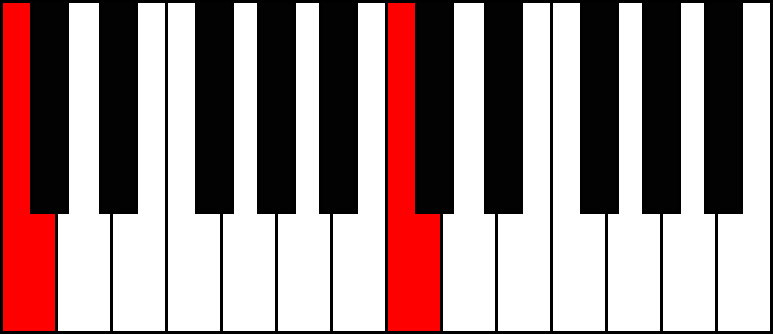

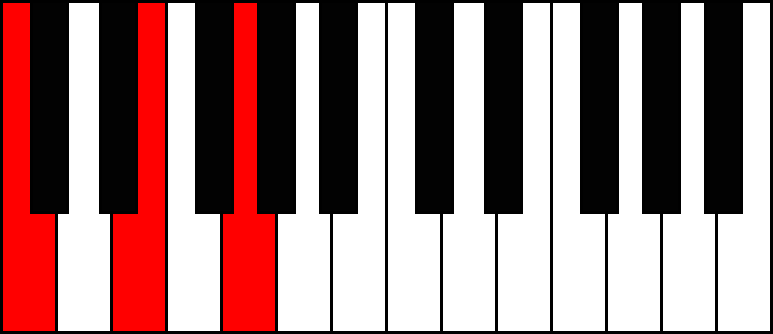

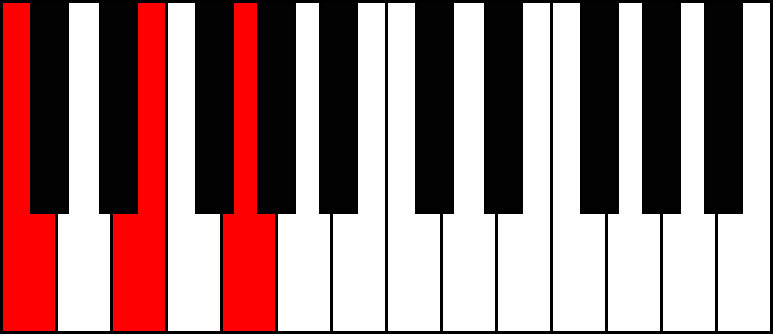

Here’s a diagram of the keyboard to help you remember the notes:

The smallest distance between two notes is called a semitone. Every step between adjacent keys (black or white) is one semitone. But intervals can be larger than one semitone—and those have specific names, which are essential for building chords later.

Here’s a list of the most important intervals:

| 0 semitones: Unison (P1) |

| 1 semitone: Minor Second (m2) |

| 2 semitones: Major Second (M2) |

| 3 semitones: Minor Third (m3) |

| 4 semitones: Major Third (M3) |

| 5 semitones: Perfect Fourth (P4) |

| 6 semitones: Tritone (TT) |

| 7 semitones: Perfect Fifth (P5) |

| 8 semitones: Minor Sixth (m6) |

| 9 semitones: Major Sixth (M6) |

| 10 semitones: Minor Seventh (m7) |

| 11 semitones: Major Seventh (M7) |

| 12 semitones: Perfect Octave (P8) |

How to Build Three-Note Chords (Triads)

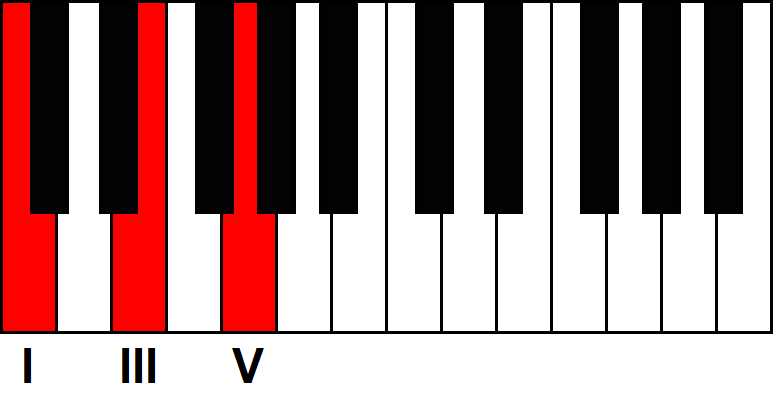

Triads are the simplest type of chords and are made of three notes, which means two intervals. Triads are built using the root note (I), a third (III), and a fifth (V).

To simplify:

A triad can be defined by the first note and the size of the two intervals.

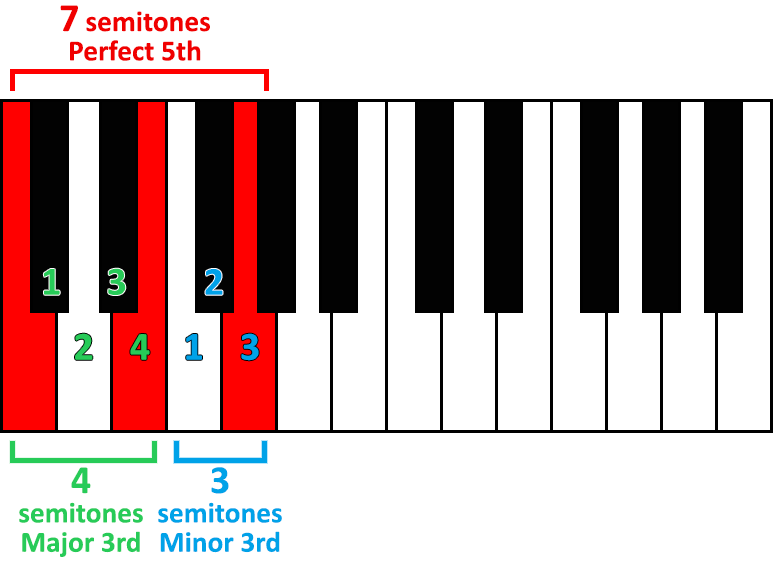

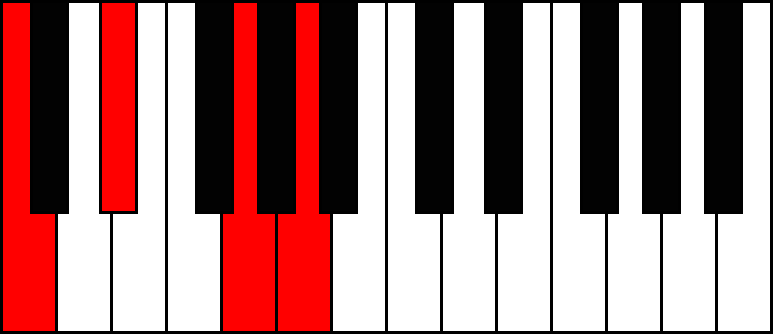

Let’s take an example: the C Major chord.

- The chord is named after its root, which is C.

- The chord type (“major”) refers to the size of the intervals.

- A major chord is built using a major third (4 semitones) and then a minor third (3 semitones).

So, to build a C Major chord:

- Root: C

- Count 4 semitones: C#, D, D#, E → (second note = E)

- Then 3 semitones: F, F#, G → (third note = G)

C Major = C – E – G

Now that you understand how to build major chords, let’s look at all the main triad types.

Three-Note Chords

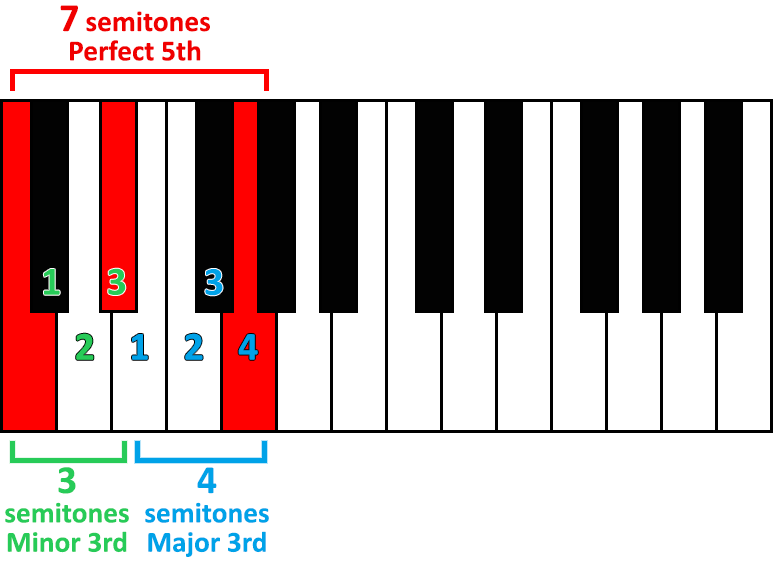

Major Chords

Major chords are built from:

- Structure: Root + Major Third (4 semitones) + Minor Third (3 semitones)

- Formula: 4 + 3

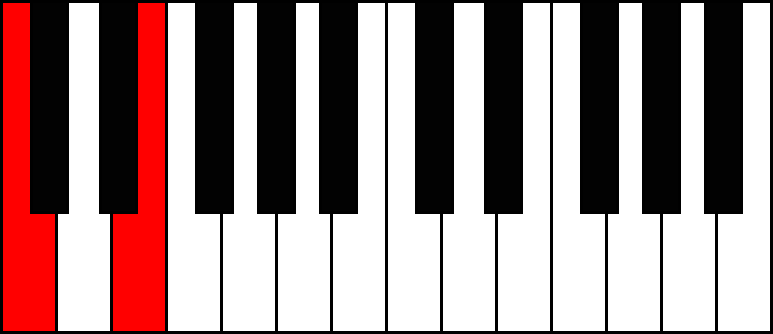

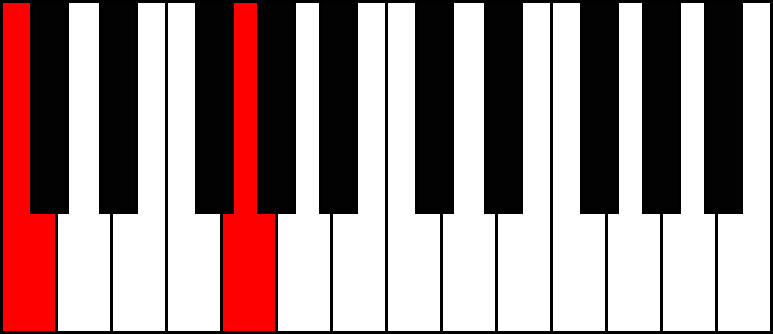

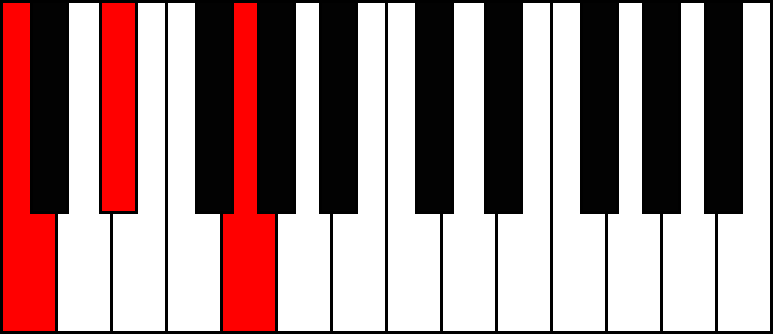

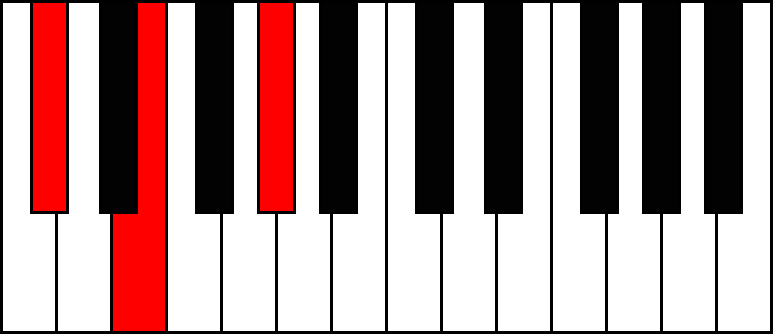

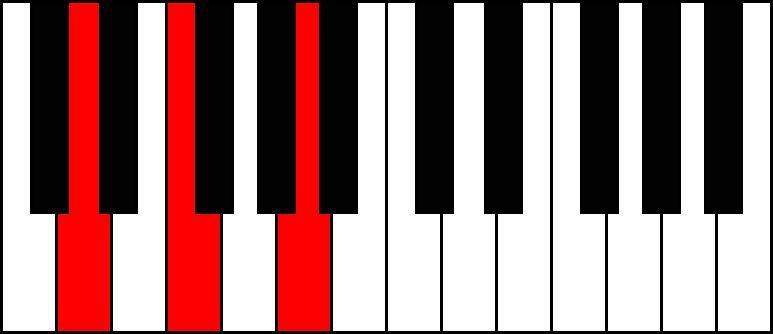

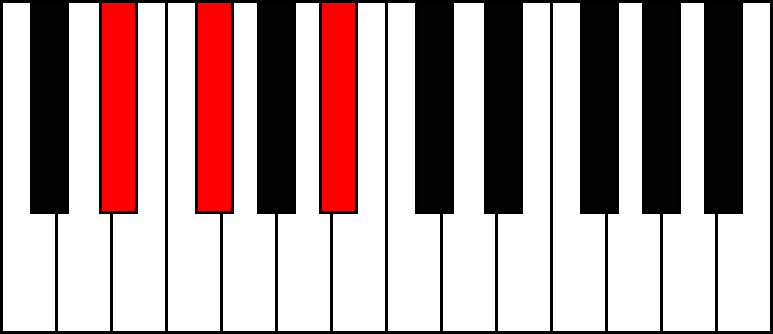

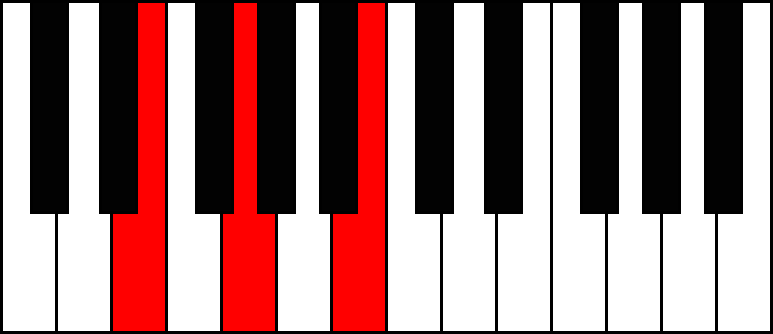

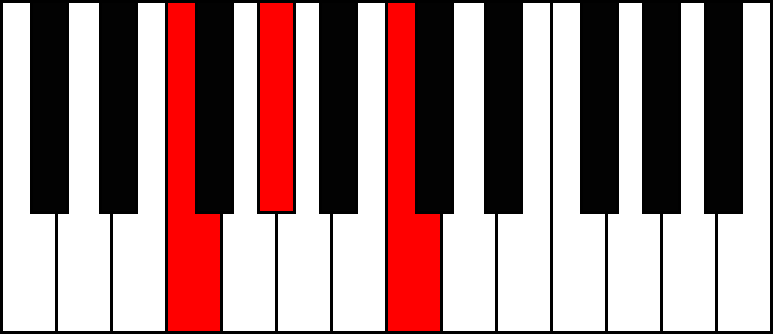

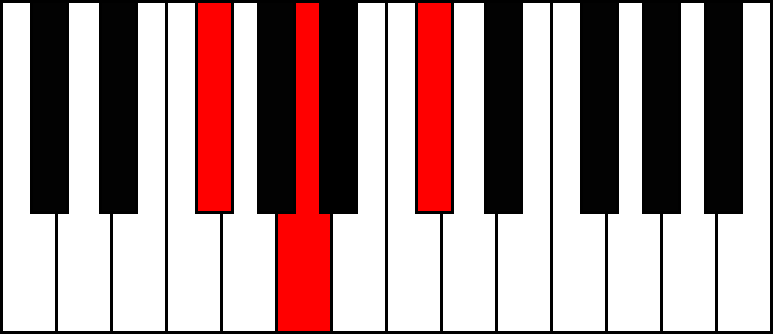

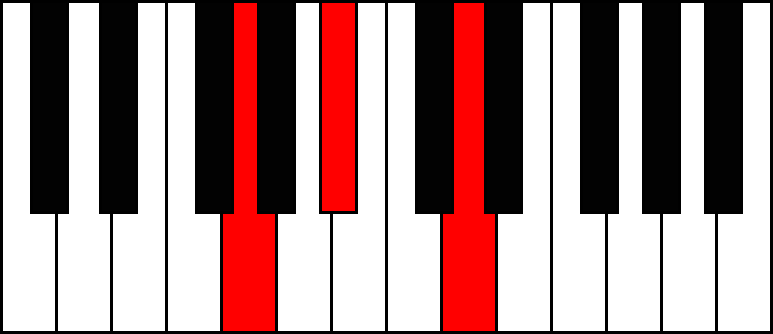

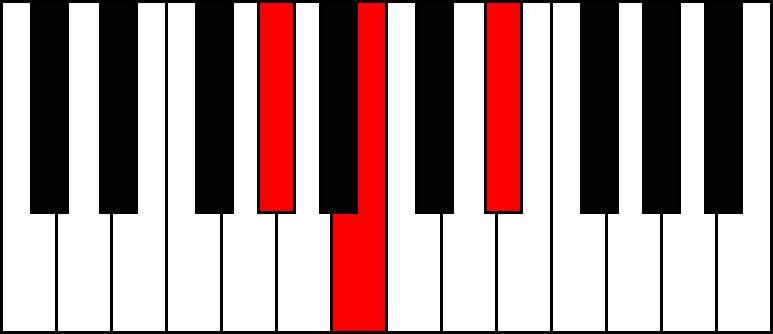

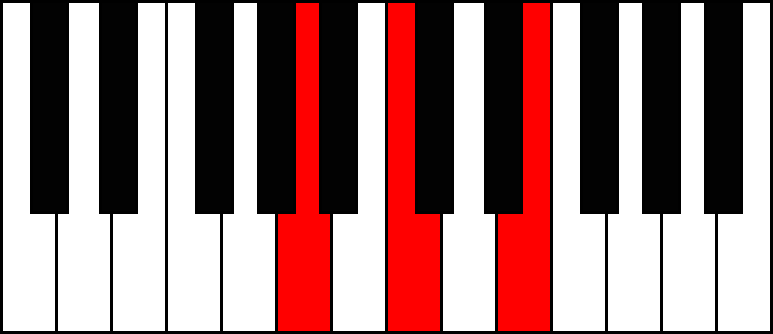

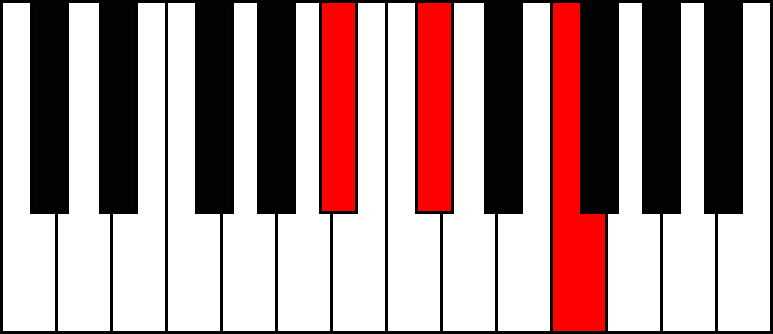

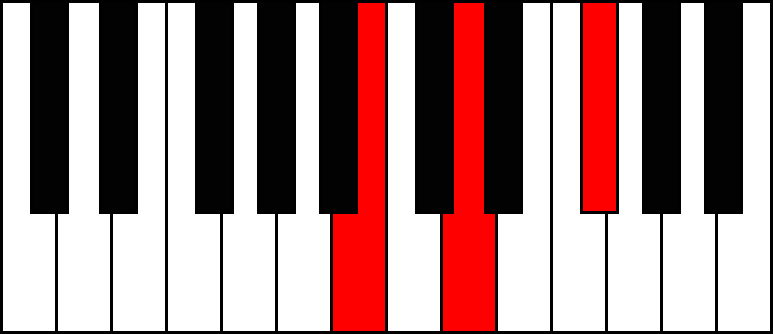

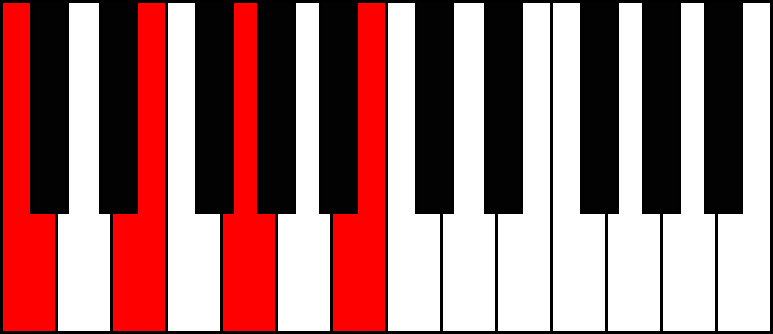

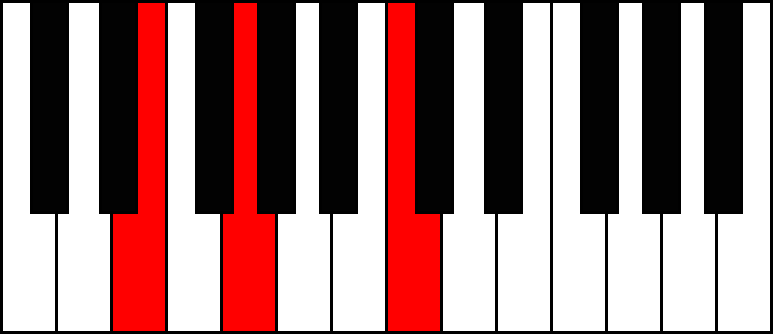

Example in C Major:

- Notation: C or CM

- Sound: Major chords sound clean, strong, and happy

Minor Chords

Minor chords are built from:

- Structure: Root + Minor Third (3 semitones) + Major Third (4 semitones)

- Formula: 3 + 4

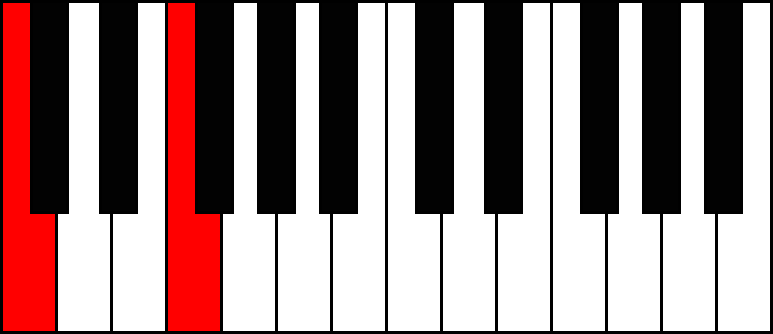

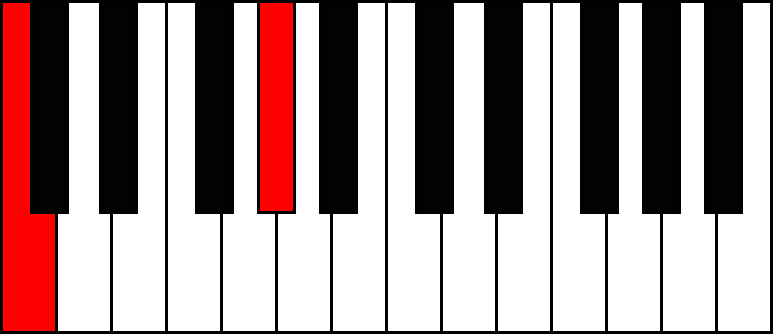

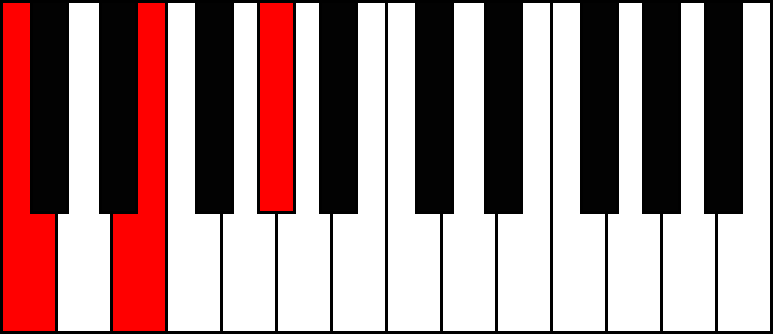

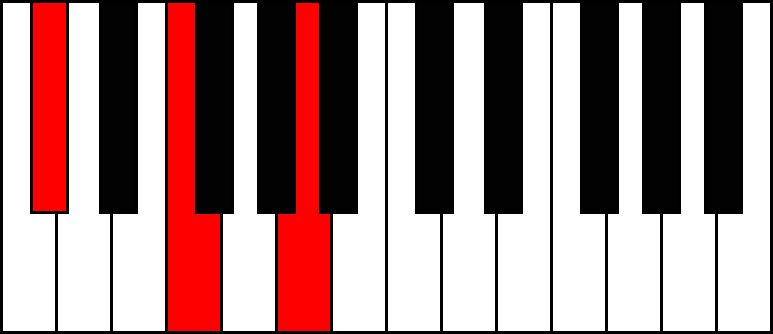

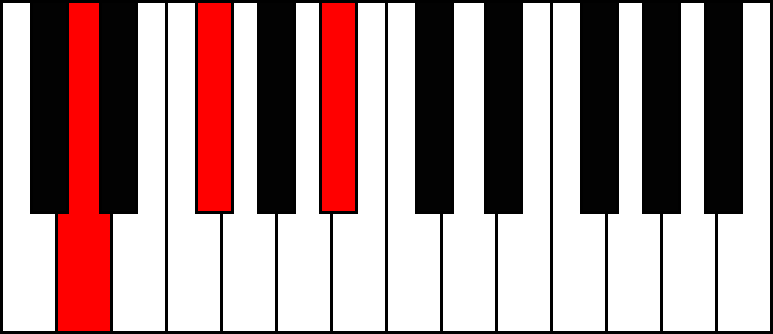

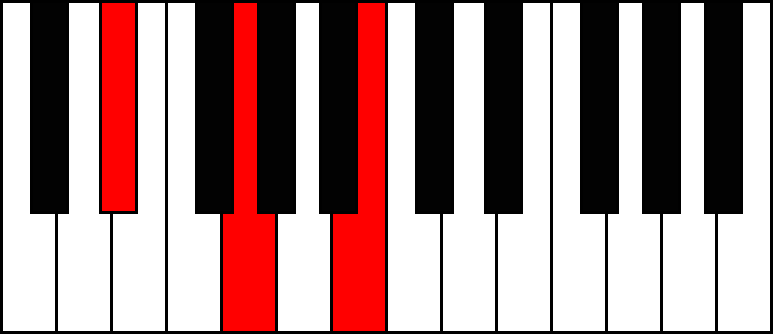

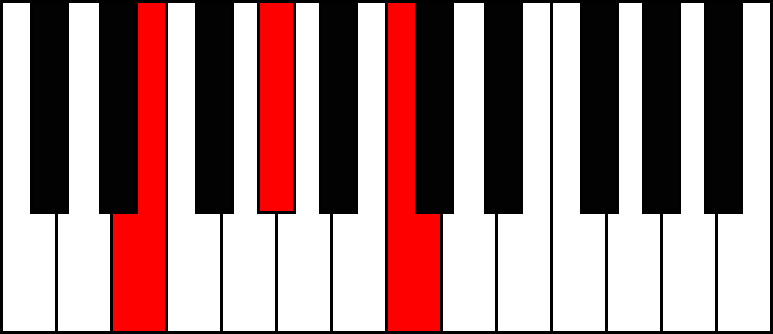

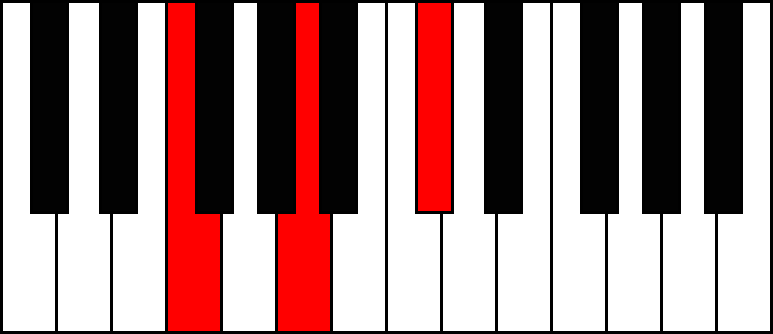

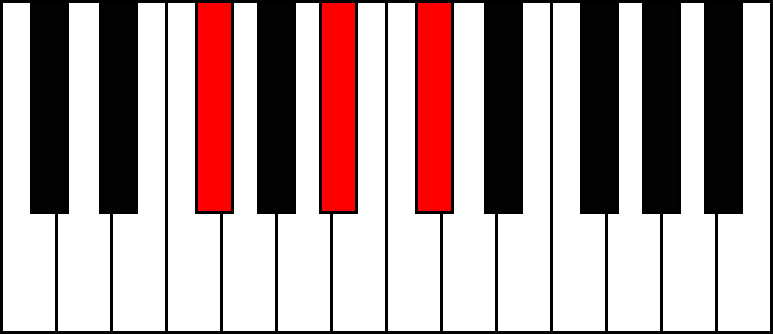

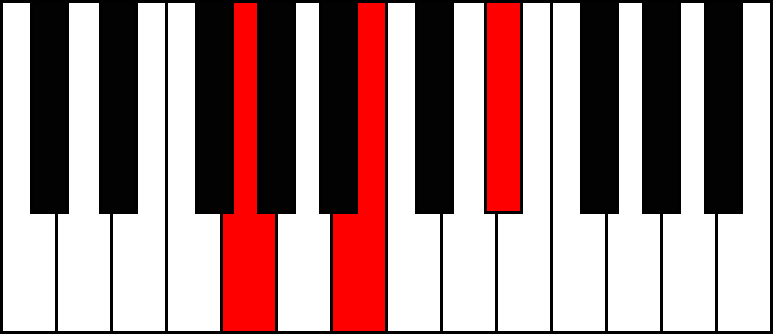

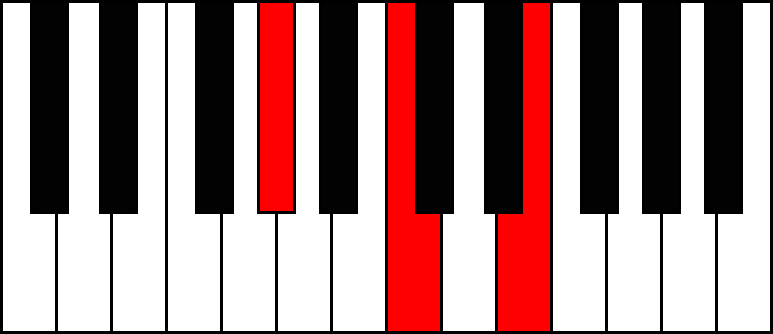

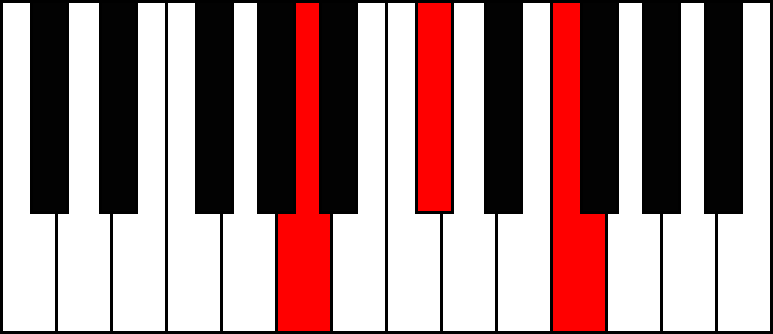

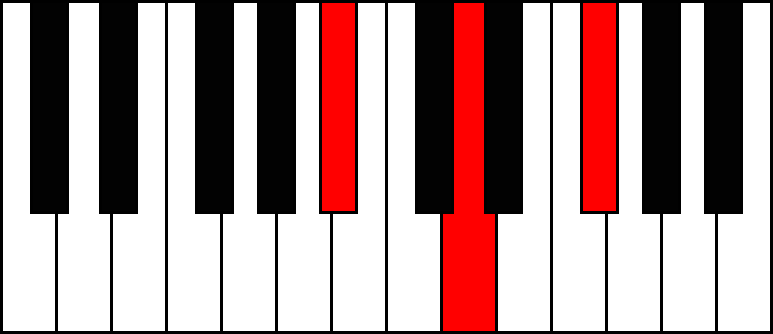

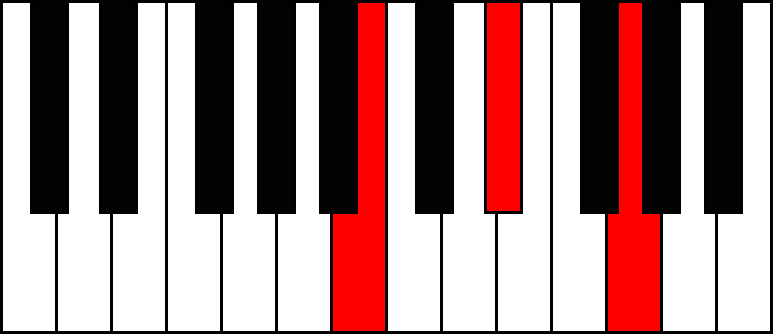

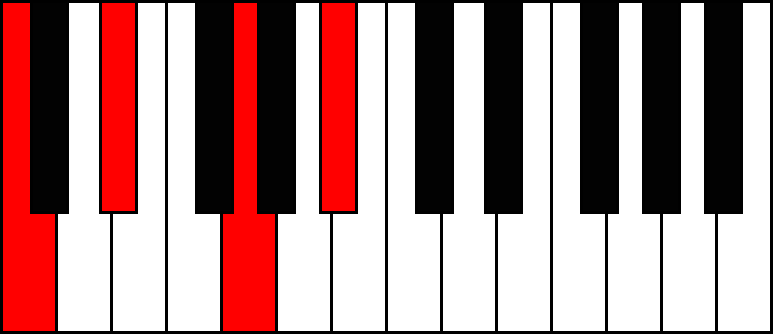

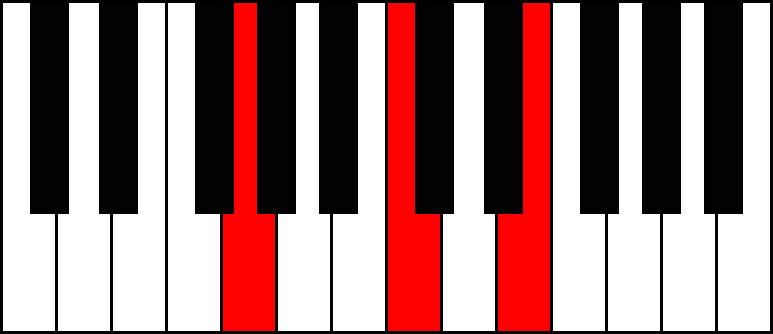

Example in C Minor:

- Notation: Cm

- Sound: Minor chords sound sad or melancholic

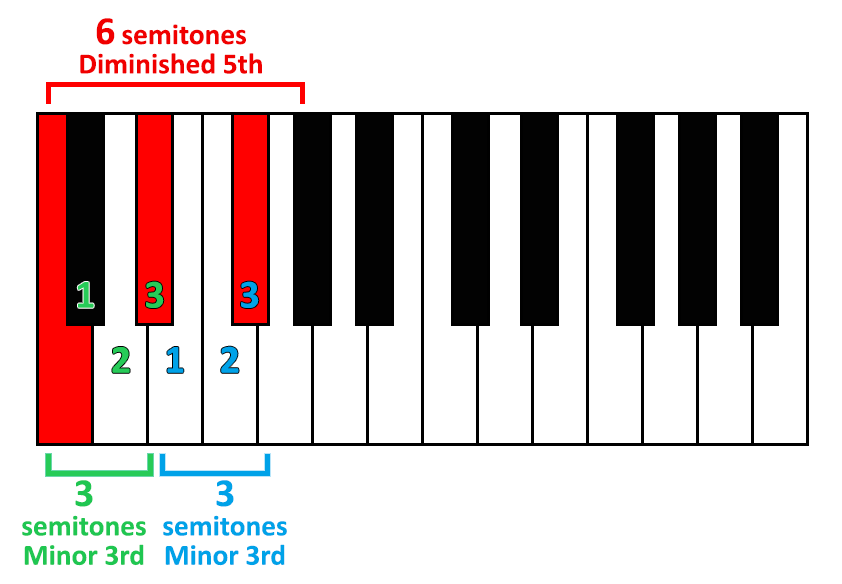

Diminished Chords

Diminished chords are built from:

- Structure: Root + Minor Third (3 semitones) + Minor Third (3 semitones)

- Formula: 3 + 3

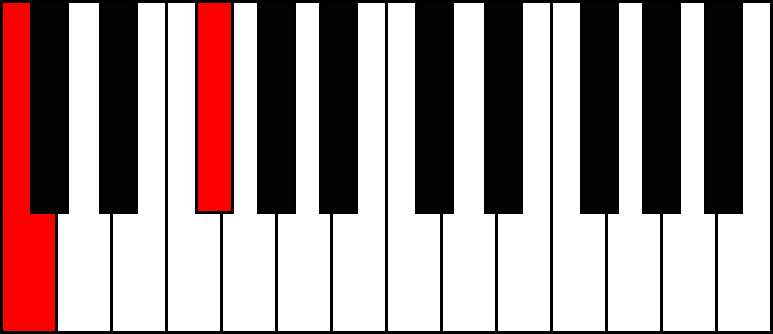

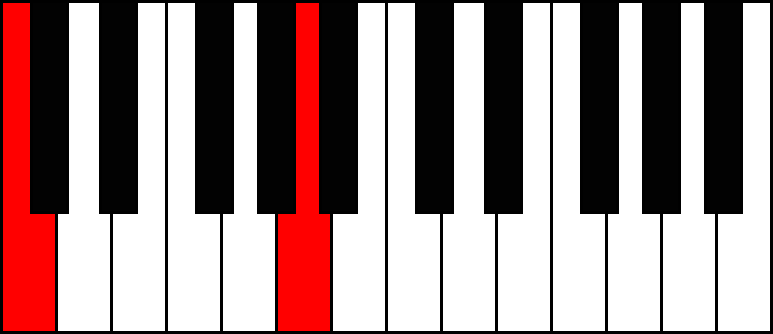

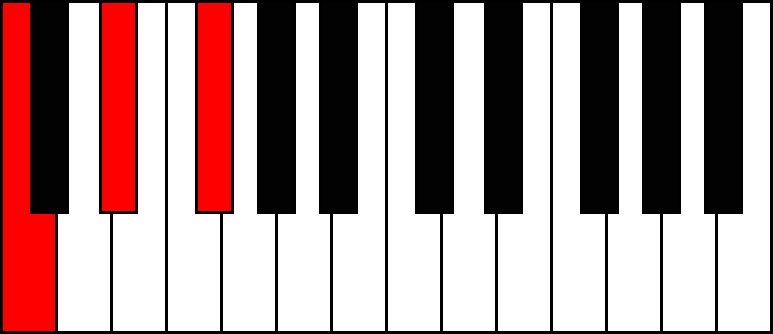

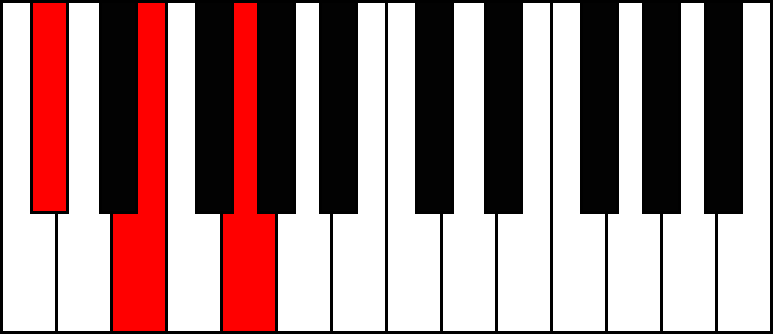

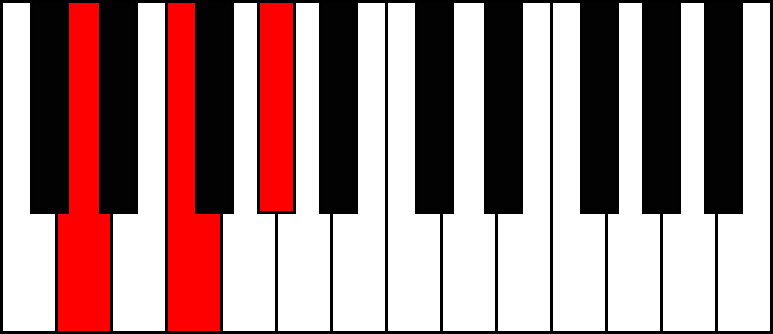

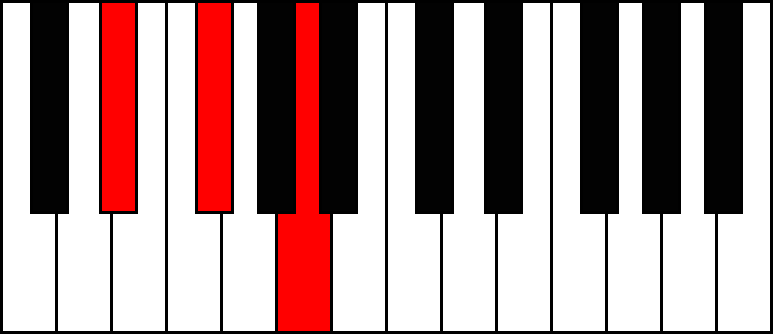

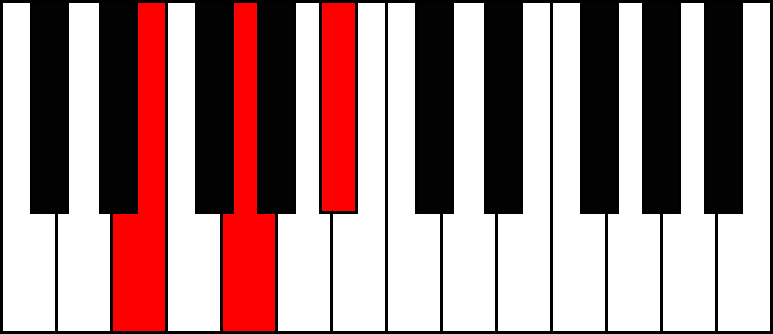

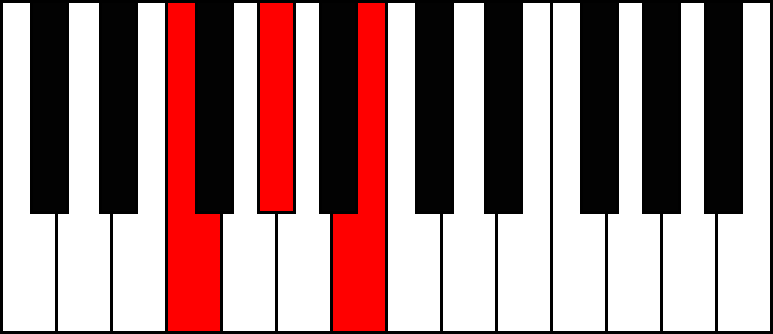

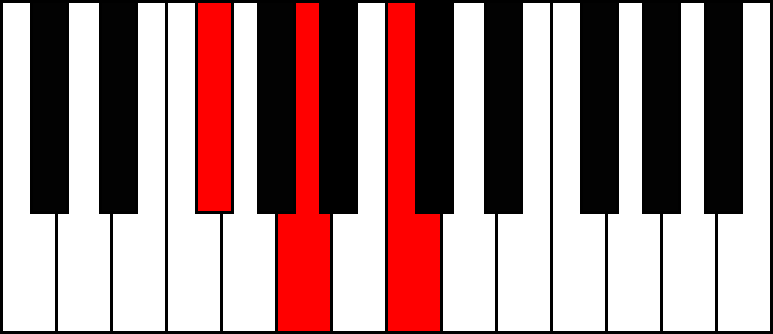

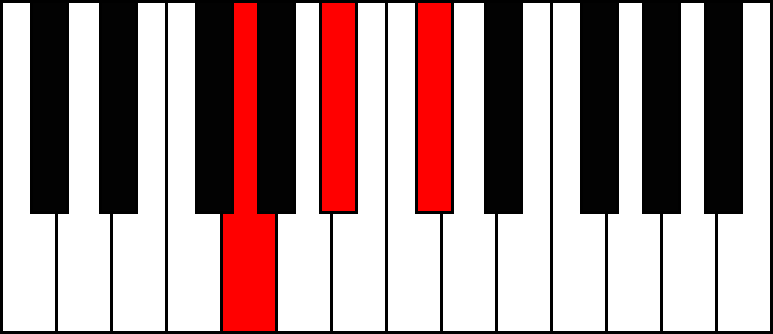

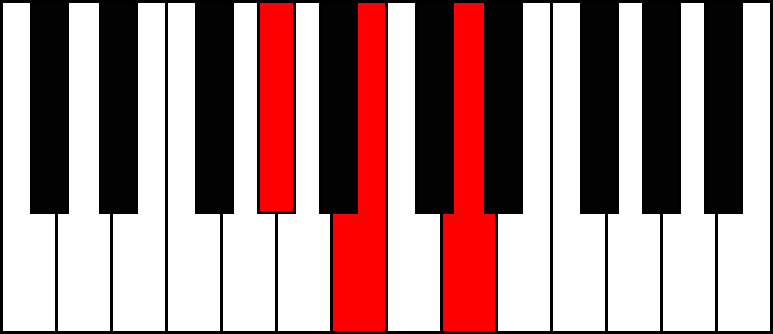

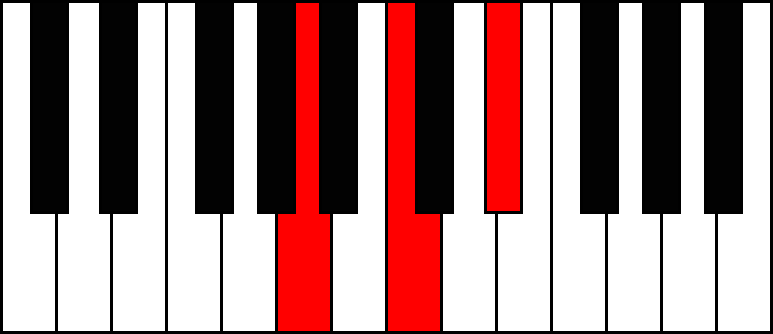

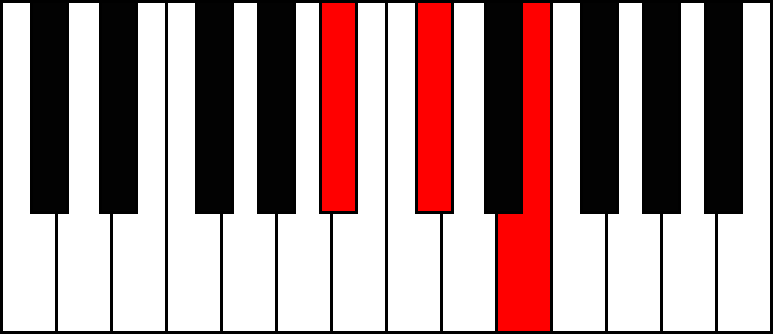

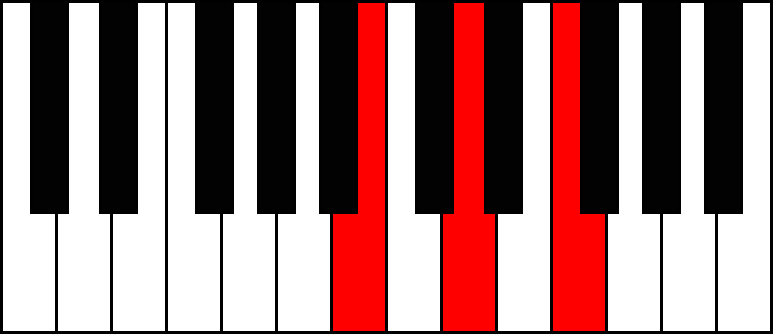

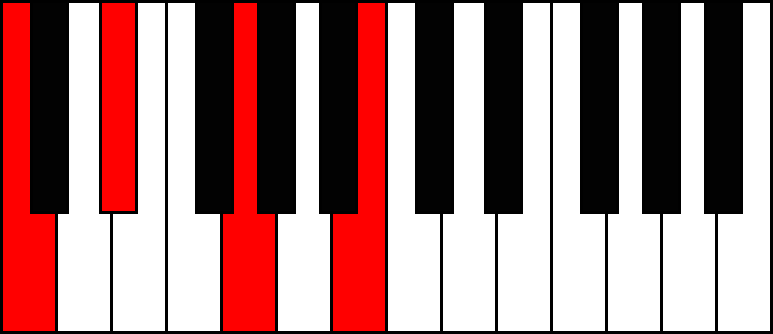

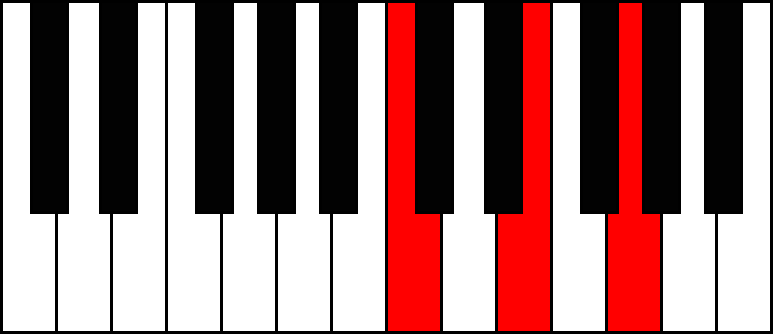

Example in C Diminished:

- Notation: Cdim

- Sound: Diminished chords sound tense or unstable

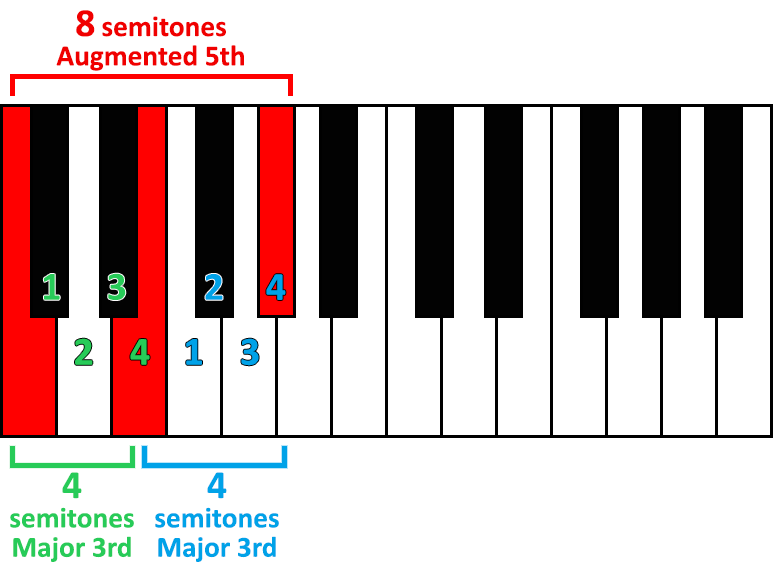

Augmented Chords

Augmented chords are built from:

- Structure: Root + Major Third (4 semitones) + Major Third (4 semitones)

- Formula: 4 + 4

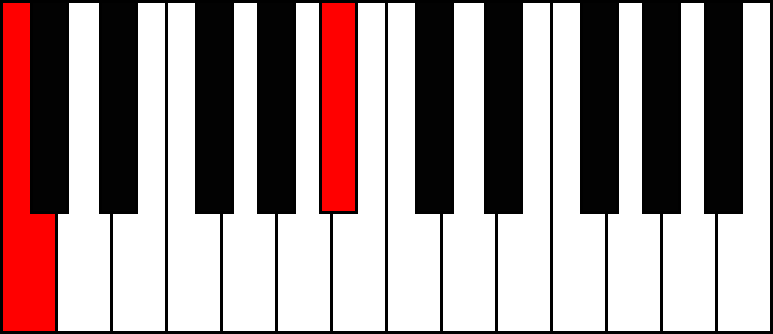

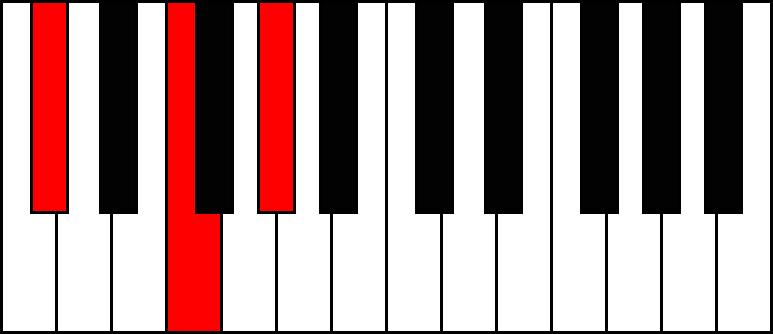

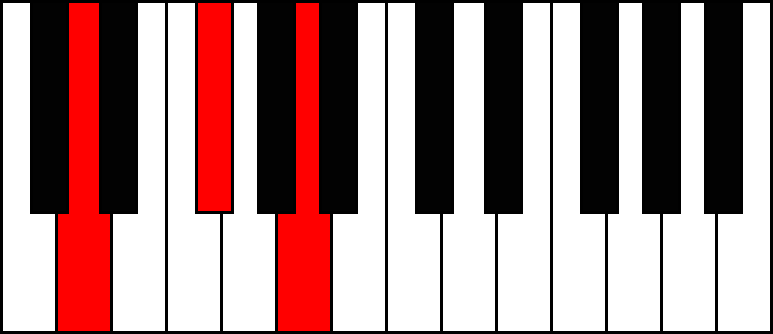

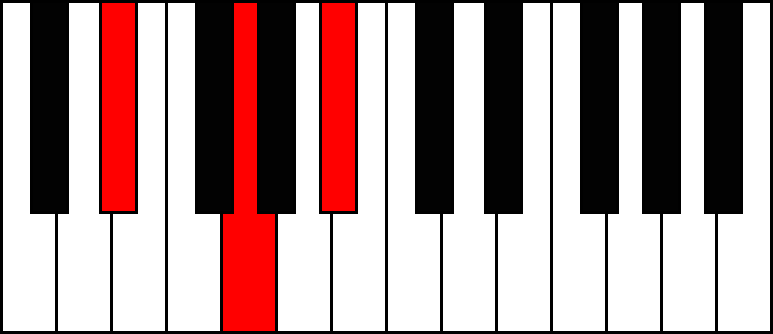

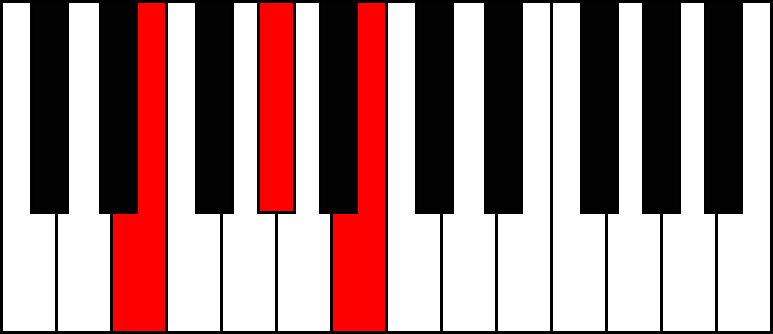

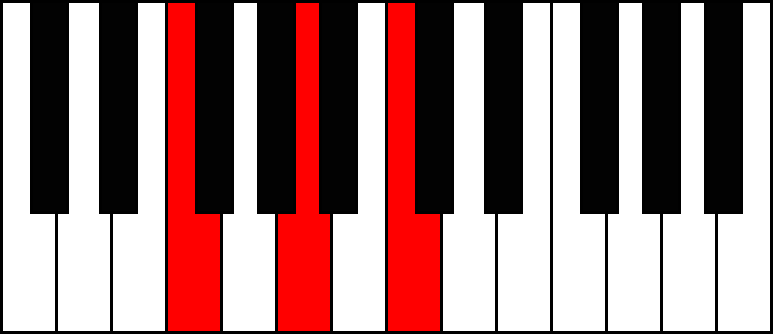

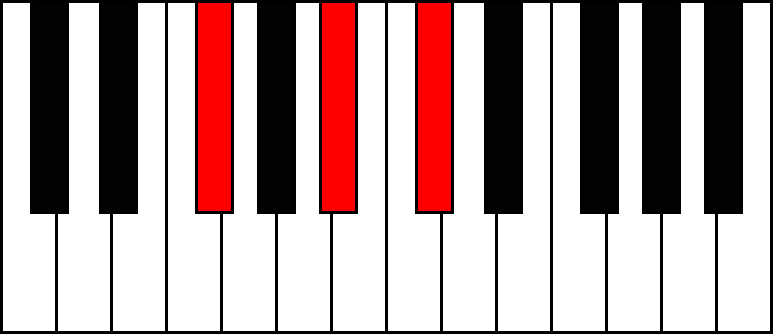

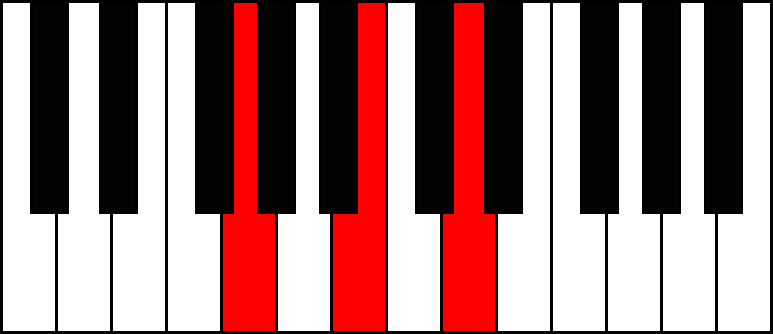

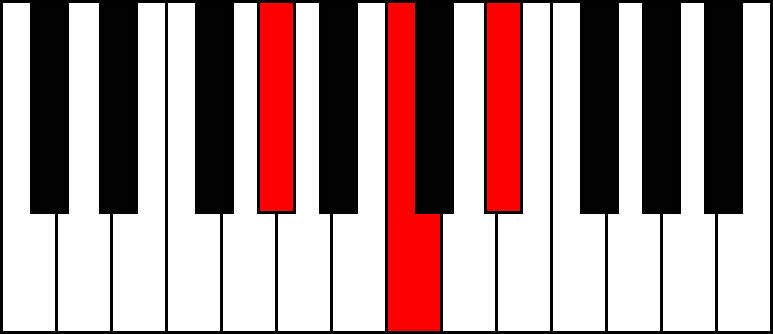

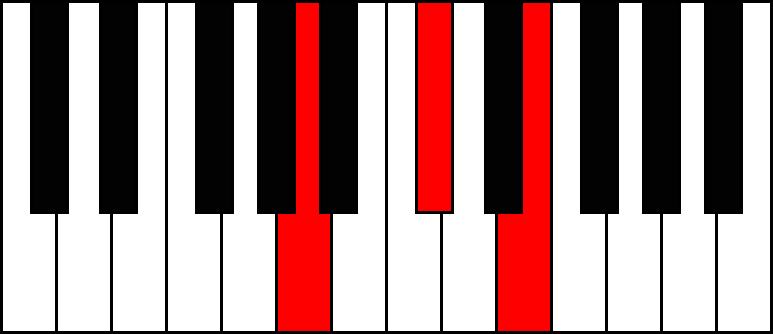

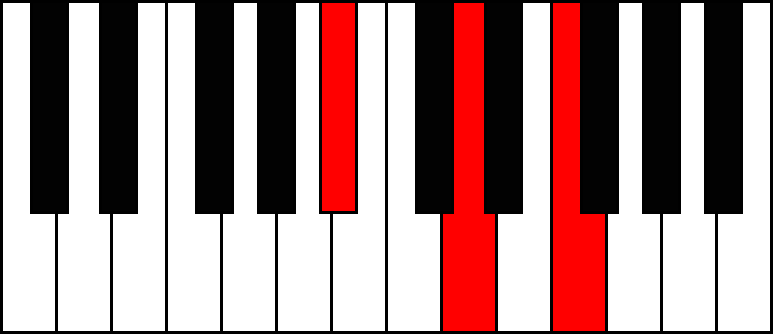

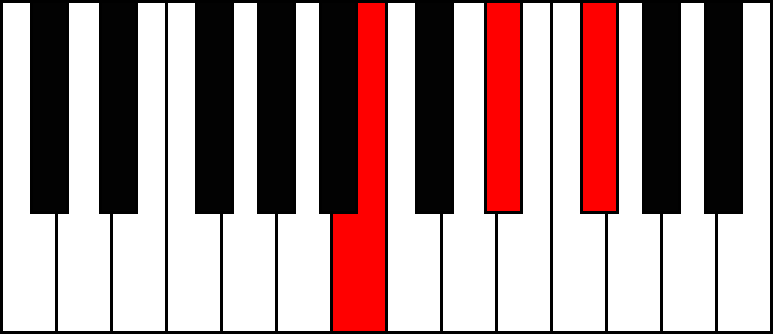

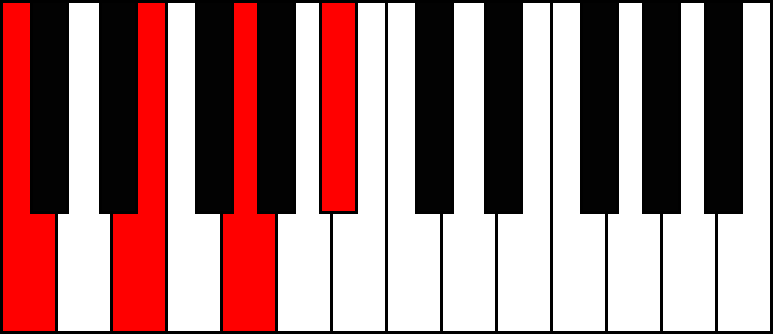

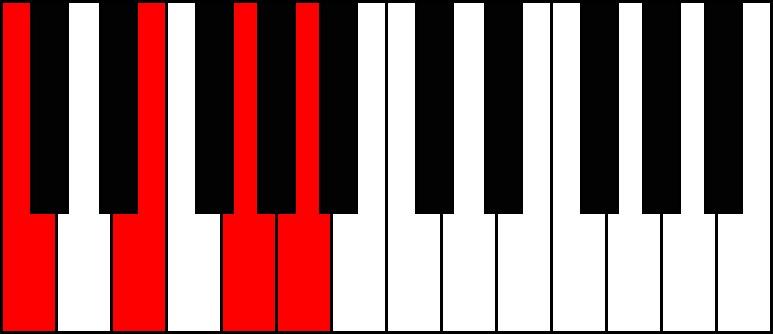

Example in C Augmented:

- Notation: Caug

- Sound: Augmented chords sound unsettling and dissonant

All Three-Note Chords

There are four main types of three-note chords (triads):

- Major chord (M) = 4 + 3

- Minor chord (m) = 3 + 4

- Augmented chord (aug) = 4 + 4

- Diminished chord (dim) = 3 + 3

The differences lie in the distance (in semitones) between the notes. These intervals determine the sound and quality of the chord.

In the next table, you can find all the triads in root position.

Full Table of 3-Note Chords

| Root | Major (M) | Minor (m) | Augmented (aug) | Diminished (dim) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C |  |  |  |  |

| C# / D♭ |  |  |  |  |

| D |  |  |  |  |

| D# / E♭ |  |  |  |  |

| E |  |  |  |  |

| F |  |  |  |  |

| F# / G♭ |  |  |  |  |

| G |  |  |  |  |

| G# / A♭ |  |  |  |  |

| A |  |  |  |  |

| A# / B♭ |  |  |  |  |

| B |  |  |  |  |

Four-Note Chords

Learning chords is essential for anyone wanting to understand harmony and express musical ideas. In this guide, you’ll discover how to build four-note chords, understand their emotional qualities, and explore extended chords and chord inversions to add richness to your playing.

Dominant 7th Chord (C7)

A dominant seventh chord (also known as a major chord with a minor seventh) consists of four notes: a root, a major third, a minor third, and another minor third stacked above. It’s called a “seventh” because the highest note is the seventh degree of the scale.

- Structure: Major triad + minor third

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 3

- Notes: Root, major third, perfect fifth, minor seventh

- Notation: C7

- Sound: Strong resolution to the tonic. Very common in blues

Major 7th Chord (CMaj7)

A major seventh chord is made of a root, a major third, a minor third, and a major third.

- Structure: Major triad + major third

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 4

- Notes: Root, major third, perfect fifth, major seventh

- Notation: CMaj7 or C∆

- Sound: Adds warmth and sophistication, often used in jazz and classical music

Minor 7th Chord (Cm7)

A minor seventh chord includes a root, a minor third, a major third, and another minor third.

- Structure: Minor triad + minor third

- Formula: 3 + 4 + 3

- Notes: Root, minor third, perfect fifth, minor seventh

- Notation: Cm7

- Sound: Adds color and depth, with a distinctive jazz feel.

Minor Major 7th Chord (CmMaj7)

This less common chord combines a minor triad with a major seventh. It includes a root, minor third, major third, and another major third.

- Structure: Minor triad + major third

- Formula: 3 + 4 + 4

- Notes: Root, minor third, perfect fifth, major seventh

- Notation: CmMaj7

- Sound: Emotional and tense, with a melancholic feel. Often used in film music and advanced jazz compositions.

Major 6th Chord (CMaj6)

A major sixth chord consists of a major triad plus a major second.

- Structure: Major triad + major second

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 2

- Notes: Root, major third, perfect fifth, major sixth

- Notation: CMaj6

- Sound: Slightly mysterious and ambiguous, ideal for adding subtle flavor to a progression.

Minor 6th Chord (Cm6)

This chord includes a minor triad plus a major second.

- Structure: Minor triad + major second

- Formula: 3 + 4 + 2

- Notes: Root, minor third, perfect fifth, major sixth

- Notation: Cm6

- Sound: Has a moody, jazzy quality. Great for introspective or atmospheric music.

Using Both Hands to Play Chords

Using one hand to play three- or four-note chords is fine. But what if you want to play chords with 6 or 7 notes? Luckily, you have two hands! The chords we’ll see next use both hands. They sound richer, fuller, and are more common in complex music like jazz — though you’ll also find them in pop and rock. It’s worth learning them to enrich your music or just to play your favorite songs.

Extended Chords: 9th, 11th, 13th

Extended chords include a note beyond the octave. Many chords can be called “extended,” especially when using both hands. But the three main types of extended chords are:

- Ninth chords (9th)

- Eleventh chords (11th)

- Thirteenth chords (13th)

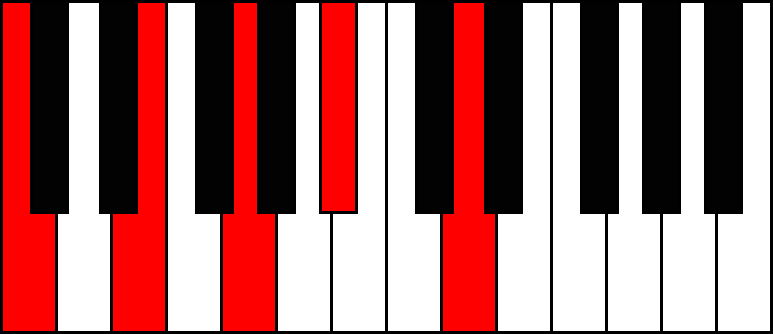

Dominant Ninth Chords (C9)

Dominant ninth chords are built by adding a major third on top of a dominant seventh chord. The highest note is the ninth degree of the scale, hence the name.

- Structure: Root + 4 semitones + 3 semitones + 3 semitones + 4 semitones

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 3 + 4

Example in C major:

- Notation: C9

- Sound: Dominant ninth chords add tension and color, often creating a sense of urgency or drama. They are common in jazz and classical music.

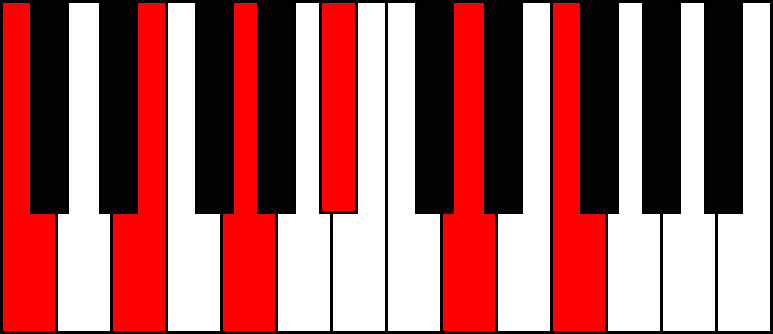

Dominant Eleventh Chords (C11)

Dominant eleventh chords are created by adding an 11th (the 4th scale degree one octave up) to a dominant ninth chord. These chords often omit the 3rd or 5th for simplicity and better voicing.

- Structure: Root + 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 5 (or 4 if we include the 11th directly)

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 4

Example in C major:

(Note: In practice, the 3rd (E) is often omitted due to tension with the 11th.)

- Notation: C11

- Sound: These chords extend the tension and richness of dominant 7th chords, offering more creative possibilities. Common in jazz and funk, and occasionally in rock.

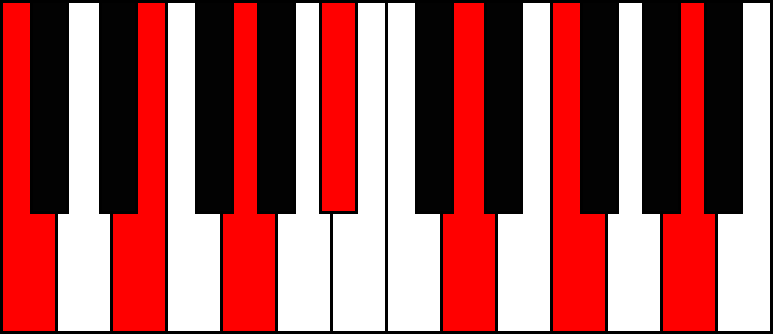

Dominant Thirteenth Chords (C13)

Dominant thirteenth chords are built by adding a 13th (the 6th scale degree an octave up) on top of a dominant eleventh chord.

- Structure: Six stacked thirds

- Formula: 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 4 + 4

Example in C major:

(Again, some notes may be omitted in actual use, often the 5th or 11th.)

- Notation: C13

- Sound: These chords are rich, expressive, and very common in jazz and R&B. They are often used to resolve back to the tonic with a soulful or colorful feel.

Chord Inversions

Once you’ve mastered basic chords, you can start experimenting with inversions. Inversions are different ways of playing the same chord by rearranging the order of the notes.

All the chords we’ve covered in the previous sections are presented in the same way: starting with the root as the first note—the note that gives the chord its name. This way of playing a chord is called Root Position. But it’s not the only way to play chords.

There are three main types of chord inversions:

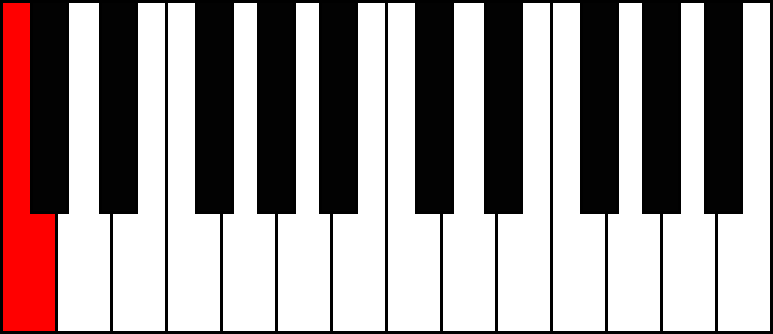

- Root position: The chord starts with the root. Example: C – E – G

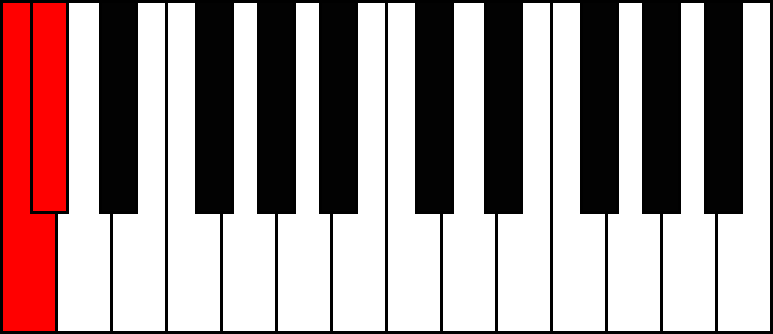

- 1st inversion: The root of the chord is moved to the top. For example, a C major chord in root position is C–E–G. In its first inversion, the C is moved to the top, resulting in E–G–C.

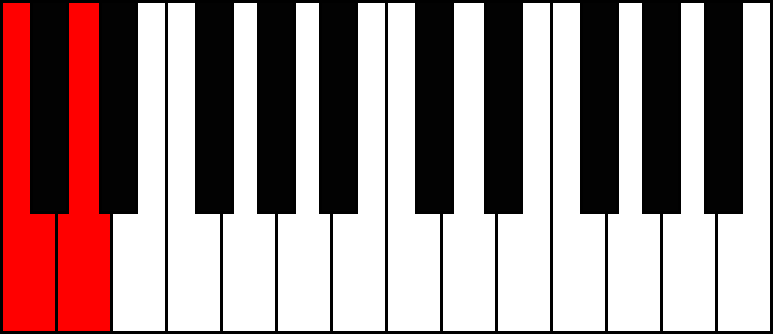

- 2nd inversion: The third of the chord is moved to the top. Continuing with the C major chord, the E is moved from the bottom to the top, resulting in G–C–E.

- 3rd inversion: The fifth of the chord is moved to the top. For a C major chord, this would be G on top, giving you C–E–G.

You might notice this is identical to the root position, but one octave higher.

So, we generally say there are three ways to play a chord: root position, first inversion, and second inversion.

This applies to triads or three-note chords. Chords with four or more notes can have additional inversions, until the original root position is reached again.

Chord inversions can add variety and smoothness to your chord progressions. They’re also useful for avoiding awkward leaps between notes when playing a sequence of chords in a song.

Tip: Inversions are especially useful for avoiding large jumps when playing chord progressions.

Common Chord Progressions

Now that you understand how chords are built and extended, let’s look at some typical progressions. Chord progressions are the backbone of most songs.

Here are a few examples:

- I–IV–V: Used in countless pop and rock songs. In C major: C – F – G

- vi–IV–I–V: A famous pop progression. In C major: Am – F – C – G

- ii–V–I: A staple in jazz. In C major: Dm7 – G7 – Cmaj7

- Minor chord progression: Darker, more emotional sound. In A minor: Am – Dm – G – E

- Suspended chord progression: Adds tension and mystery. Example: Csus2 – Csus4 – Cmaj7

- Extended chord progression: More color and complexity. Example: Cmaj7 – Dm7 – G9 – Cmaj7

Note:

Uppercase Roman numerals = Major chords

Lowercase Roman numerals = Minor chords

Tips for Practice

The best way to learn piano chords and progressions is through consistent practice. Start with basic chords like major, minor, and dominant sevenths. As you become more comfortable with them, you can move on to extended chords and more complex progressions.

Here are some tips for practicing:

- Memorize chord shapes: This helps you change chords more easily.

- Practice inversions: Improve your hand flexibility and voice leading.

- Play real songs: Use chord sheets or lead sheets to see how chords work in context.

- Create your own progressions: Try combining chords in new ways.

- Active listening: Try to identify chords in the songs you love.

Remember: Learning piano chords takes time and repetition. Don’t be discouraged if it feels slow at first. The more you play, the more natural it becomes. Enjoy the journey of discovering new sounds and musical possibilities!